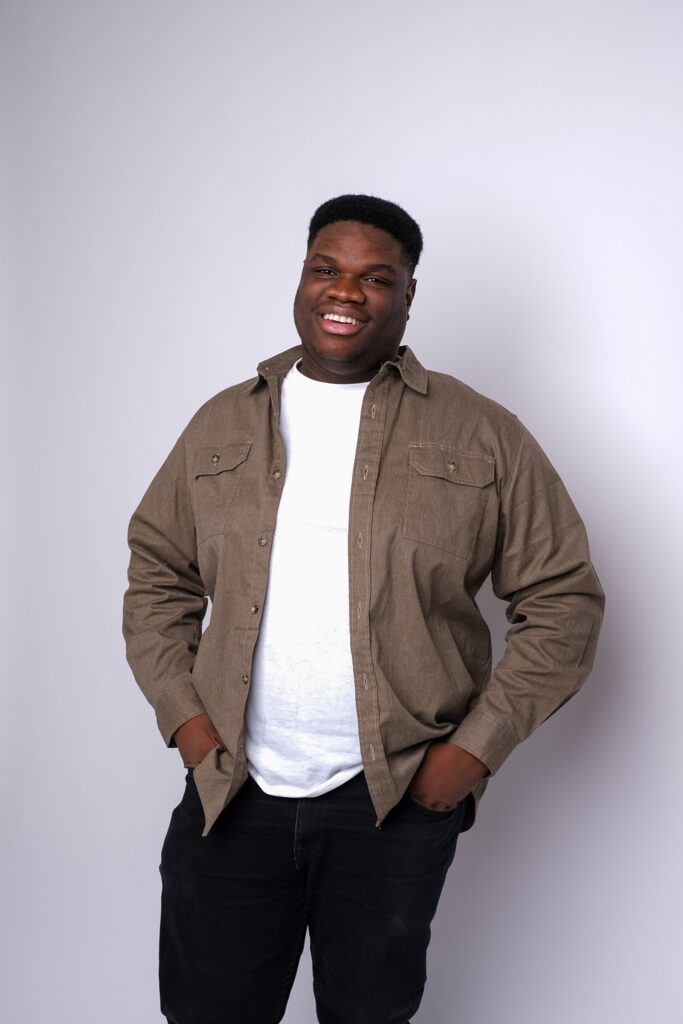

Faces of BME - Ferdinand (Reke) Avikpe

Ferdinand (Reke) Avikpe, originally from Warri, Nigeria, came to Canada at 15 to pursue undergraduate degrees at the University of Winnipeg. His early immersion in academia, with a focus on biochemistry and mathematics, was both challenging and rewarding, shaping his approach to learning. Despite initial struggles with cultural adjustment and academic differences, he quickly adapted, excelling in his studies and embracing opportunities for growth. Passionate about design and visual storytelling, Ferdinand explored his creative side through extracurricular activities and roles like Director of Marketing for the Golden Key International Honour Society. He also delved into AI research, focusing on computational models of stem cell differentiation under Dr. Cristina Amon at the University of Toronto.

You came to Canada at 15 to attend an undergraduate degree at the University of Winnipeg. What was that experience like?

Starting my undergraduate journey at the University of Winnipeg at 15 was transformative. Initially, my age felt like a drawback, fearing judgment from peers and professors. However, academically, while Canadian standards seemed less rigorous compared to Nigeria, I thrived, completing two Bachelor's degrees in three years with exceptional performance. The shift in educational systems challenged me to adapt quickly to a higher level of critical thinking. Access to resources and practical learning opportunities in Canada starkly contrasted my previous experiences. Moreover, the informal approach of Canadian professors was a pleasant surprise compared to the rigid hierarchy in Nigeria.

Socially, integrating into university life was daunting, but overcoming language barriers and stepping out of my comfort zone fostered growth and confidence. Despite its harsh winters, the Winnipeg community offered warmth and hospitality, enriching my overall experience. The University of Winnipeg provided a nurturing environment with small class sizes and a focus on inclusivity, allowing me to flourish academically and professionally. Reflecting on this journey, I've learned valuable lessons in resilience, adaptability, and seizing opportunities, shaping me into the person I am today.

What’s your graduate research topic?

I work in the lab of Dr. Cristina Amon, former Dean of the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering, and cross-appointed to the Institute of Biomedical Engineering. My research is centered on developing sophisticated in silico or computational models that simulate the differentiation processes of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). These models are designed to understand how these cells evolve into lung progenitors and cardiomyocytes, critical for lung and heart tissue development. This complex process is meticulously charted out through the various stages of cellular differentiation, with the models predicting both the pathways and the timing of these changes. By employing systems of ordinary differential equations, the models integrate a range of biological and environmental variables to mirror the intricate realities of cell development. By simulating diverse experimental scenarios, the models seek to optimize cell culture conditions, streamline experimental protocols, and improve the design of bioreactors. This optimization will lead to improved cell yields and reduced costs, which are crucial steps towards practical clinical applications. This work represents a synergy of biology, mathematics, and statistical methods, aiming to improve our understanding of pluripotent stem cells, which is vital for advancements in regenerative medicine and therapeutic applications.

What is your home city in Nigeria? How would you describe it to people who have never been there before?

I was born and raised in Warri located in Delta State, the southern part of Nigeria. When you mention that you’re from Warri to a fellow Nigerian, they look at you different. This is because in general, people from Warri tend to be hyperactive. Warri is a vibrant city with a spirit that is as energetic as the flow of the Warri River that runs through it. Warri is a melting pot of various ethnicities and cultures, predominantly inhabited by five tribes: Urhobo, Isoko, Ijaw, Itsekiri and Delta Igbo. My dad is from the Isoko tribe and my mum is from the Urhobo tribe. This diversity is reflected in the city’s rich tapestry of customs, languages, and of course, delicious cuisines.

Warri might not have the sprawling skyline of more prominent cities in Nigeria, but it has a bustling atmosphere that’s full of life. It’s a city where laughter is never far off, and the air carries the comforting aroma of street food like bole (grilled plantain), and fried fish. Walking through the streets, you’ll be greeted with the warm smiles of the locals and the rhythmic beats of Afrobeat music coming from shops and homes.

Despite being a crude oil hub, Warri retains its natural beauty, with lush mangroves and a scenic waterfront. To those who have never been to Warri, I often describe it as a city of resilience and joy. It has faced its share of challenges, but its spirit remains undimmed. The people here are some of the most hospitable you’ll ever meet, always ready to share a story or a meal. Warri may not be a typical tourist destination, but it’s a place that truly feels like home.

Can you teach us some jargon used in Nigeria?

Nigeria is a country of incredible diversity, a true mosaic of cultures. Comprising 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory in Abuja, it is a country with over 250 ethnic tribes, each with its own distinct language, sub-languages (dialects) and customs. The three main tribes in Nigeria are the Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa tribes. Nigeria’s cultural richness is reflected in its many languages – there are about 500 spoken across the country, adding to its vibrant heritage and dynamic society.

Despite the multitude of languages, one unifying tongue that stands out is Nigerian Pidgin English. Often referred to simply as ‘Pidgin’, it’s a creole language that evolved from the contact between English and various ethnic languages. It serves as a lingua franca in many parts of Nigeria, particularly in urban areas and the Niger Delta region where my hometown of Warri is situated.

Pidgin is characterized by its unique expressions, intonations, and the adoption of words from the myriad of English and indigenous languages. It is a language that carries with it the flexibility and creativity of the Nigerian people. Here are some common slangs in Nigerian Pidgin and their meanings:

How far?

This is a greeting that’s equivalent to “How are you?” or “What’s up?”

I dey

It’s a response to “How far?” that means “I’m fine” or “I’m here.”

No wahala

It means “No problem” or “It’s okay.”

Abeg

A word that translates to “Please.”

Wetin dey happen?

This phrase means “What’s happening?” or “What’s going on?”

E go better

An expression of hope or encouragement, meaning “It will get better.”

Chop

Means “to eat,” but can also refer to making money, depending on the context.

Oga

It refers to a boss or someone in a position of authority.

JJC

Stands for ‘Johnny Just Come’, used to describe a newcomer or someone naive about the ways of a place.

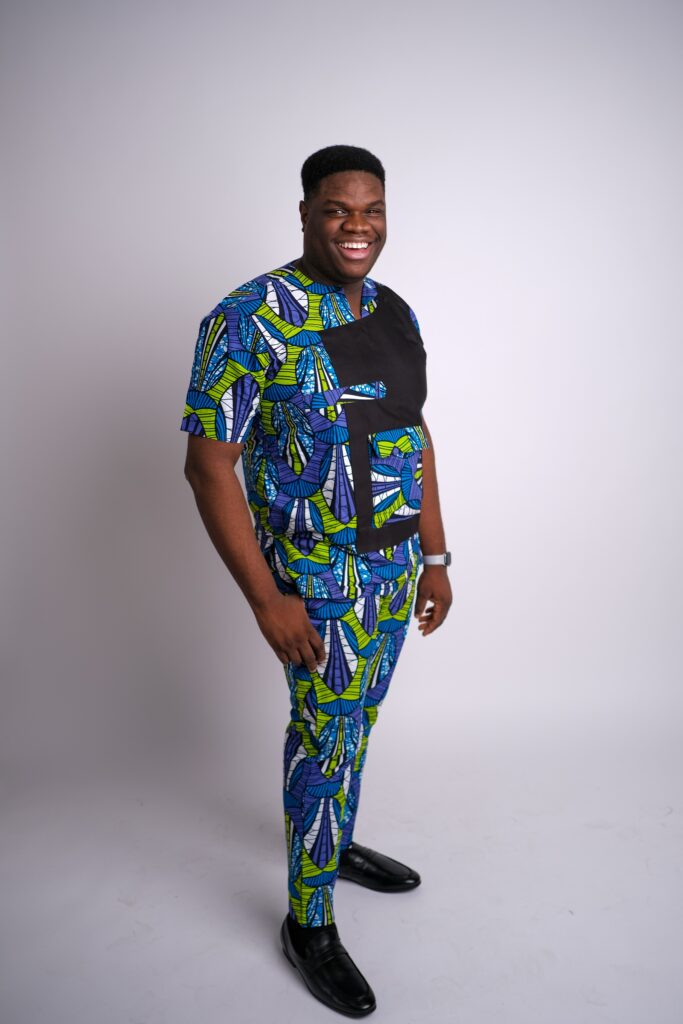

Are there any traditional attires you would like to showcase? What types of occasions would you wear them?

Each ethnic group in Nigeria has its distinct attire reflecting their unique identity. Typically, Nigerian attires are worn for formal events like weddings, religious ceremonies like church services, funerals, and important social gatherings.

Some staple Nigerian attires for men include Ankara, Dashiki and Senator style clothing.

Ankara

Among Nigeria’s traditional attire, the Ankara fabric stands out for its versatility and vibrancy. Ankara is a cotton fabric characterized by its colorful patterns and designs, which have become synonymous with African fashion on the global stage. It is used to make a wide range of garments, including dresses, trousers, skirts, blouses, and even accessories like bags and shoes.

In Nigeria, Ankara is worn with pride across various occasions, transcending age and gender. It is a popular choice for everyday wear due to its comfort and the way it effortlessly accommodates different styles. For more formal events like weddings, naming ceremonies, and religious services, Ankara is tailored into exquisite designs that often include intricate embroidery and embellishments. The one I am wearing was made for my grandma’s funeral. It is not uncommon to see entire families dressed in matching Ankara outfits for special events, symbolizing unity and a shared sense of fashion.

In addition, it is very common for Ankara to be referred to as ‘Aso-ebi’. Aso-ebi is a Yoruba term that translates to ‘family cloth’ and is a Nigerian tradition that involves groups of people wearing a uniform dress to signify their close relationship to the celebrants at a social gathering or ceremony. It is a common sight at Nigerian weddings, funerals, christenings, and significant birthdays, symbolizing solidarity and unity during the event.

The practice of Aso-ebi involves the celebrant or family choosing a specific fabric and color scheme which their family members, friends, and sometimes, even acquaintances, will purchase and tailor into outfits for the occasion. These garments are often made from luxurious fabrics such as lace, ankara, or aso-oke, the latter being a traditional hand-woven cloth originating from the Yoruba people.

Wearing Aso-ebi is a powerful expression of community and belonging. It visually denotes the connection of the group to the celebrant and adds to the vibrancy and beauty of Nigerian festivities. The uniformity in attire also creates an impressive visual impact at social events, with beautifully dressed guests in coordinated fabrics and colors.

In modern times, the Aso-ebi tradition has evolved, becoming a fashionable phenomenon that encourages creative and stylish interpretations of the chosen fabric. This custom not only reinforces social bonds but has also become an integral part of Nigeria’s fashion industry, influencing trends and driving innovation in textile design and tailoring.

Senator Dashiki

‘Dashiki’ is a colorful men’s shirt that’s also embraced by women. It’s casual enough for everyday wear but can be dressed up for special occasions.

The ‘Senator’ style is a modern twist on traditional wear. It is a plain or slightly patterned simple, short or long-sleeved kaftan suit that’s become a staple for contemporary Nigerian men, perfect for business meetings or casual outings. It is called ‘Senator’ style clothing because it is worn by a lot of Nigerian Senators.